[all opinions expressed are my own]

Recently, I’ve been followed around by a bad smell. A gassy one.

Everywhere I look in the supply chains of some of fashion’s most powerful and profitable companies, gas is fuelling the production of billions of new garments every year*. From LNG (liquified natural gas) tanks permanently installed at textile processing facilities in Taiwan, ready to be burned to heat water for batch dyeing fabrics, to Bangladesh importing expensive LNG from India to meet the skyrocketing energy needs of thousands of RMG factories. A lack of transparency from fashion brands on the energy consumption profile of their supply chains makes reliable statistics impossible to find, but we know that fossil fuels reign supreme in fashion. We also know that gas is a fossil fuel that’s becoming increasingly popular amidst pressure to reduce emissions.

*How many billions? We’re not sure. That’s why we needed brands to #SpeakVolumes.

Before we start, a note on ‘natural’ gas from climate reporter Emily Atkin, who says it much better than I can:

“After all, most people think things that are called “natural” are good for the environment—and natural gas is objectively not.”

…and check out Atkin’s recommended resources on why we should probably avoid playing into the hands of fossil fuel companies by calling it ‘natural gas’:

How the gas industry aims to rebrand as ‘clean’ energy to appeal to Black and Latino voters

Different names for “natural gas” influence public perception of it

Fossil fuel executives see a ‘golden age’ for gas, if they can brand it as ‘clean.’

Gas as a credible decarbonisation strategy (or more like a ‘not-good-but-less-bad’ bridge fuel) is a surprisingly popular narrative in the fashion industry. Despite the fact that fashion manufacturing is far from a hard-to-abate sector like aviation, shipping, steel or cement. For example, a new book entitled The Path to Net Zero for the Fashion Industry suggests that the first step to decarbonisation should be to ‘remove coal and replace it with natural gas, which will immediately reduce GHG emissions by around 50%’.**

While it may be tempting to say ‘look, we don’t have all the answers for 100% renewable electricity right now, so let’s switch out burning one fossil fuel for another while we figure it out (mostly so our sustainability reports still look good)’ - this argument is a classic example of short-termism that fails to consider the consequences on people (toxic air pollution from burning gas, land rights exploitation from fracking), politics (foreign gas dependence, resource conflicts) and planet (even with gas, absolute emissions will continue to rise!!!). Ultimately, we need to set our sights on a just energy transition that sets us up for long-term success, which means breaking up with all fossil fuels and investing in clean, green energy.

As Rachel Cernansky remarked in a 2020 article on coal phaseout in fashion supply chains: “Energy experts worry the industry will focus on making existing boilers more efficient or turning to greener*** fuel options, like natural gas, that may reduce coal consumption but not ultimately solve the problem.” Fashion decarbonisation expert Michael Sadowski added: “We can’t afford to do this on a stepwise basis. Gas will reduce emissions, but it’s not a path to decarbonisation.”

It makes sense that gas is being used in this way because textile and garment suppliers are struggling to meet climate targets dictated to them by brands, without any financial support for cleaner alternatives****. But instead of accepting this status quo, we need to look at the science. Climate scientists have told us in no uncertain terms: fossil fuels cause climate change, and we must phase them out in order to mitigate the most catastrophic effects of the climate crisis. So even if gas offers a quick emissions reduction on paper, can we really afford to lock the fashion industry into more fossil fuel reliance if we are serious about ‘net zero by 2050’, as corporate sustainability reports and countless multi-stakeholder commitments claim to be?

**When burned, gas releases about half as much carbon dioxide as coal, but methane traps about 85 times more heat than CO2 over a 20-year period.

***Maybe we should try switching out ‘more sustainable’ with ‘less unsustainable’ in more of these conversations.

****Obviously, fashion brands need to cough up. They can afford it.

The root problem here is the framing of gas as a ‘bridge fuel’ towards a beautiful, clean 100% wind and solar-powered fashion industry that will somehow magically materialise even if we invest no time, energy and money into it (?!?). This framing within the fashion industry directly feeds into the carefully constructed PR efforts of fossil fuel executives. No really - Ryan Lance, chief executive of ConocoPhillips said at a conference recently: “Gas is something that’s going to be more than just a bridge fuel. It’s going to be around for a long time.” Commenting on this,

reminds us:“The fossil fuel industry’s growing campaign to brand gas as “clean energy” is no different from its old campaign to brand climate change as fake. Both were created to dampen public demand for effective climate policy, which would necessitate the phase-out of their highly profitable products.”

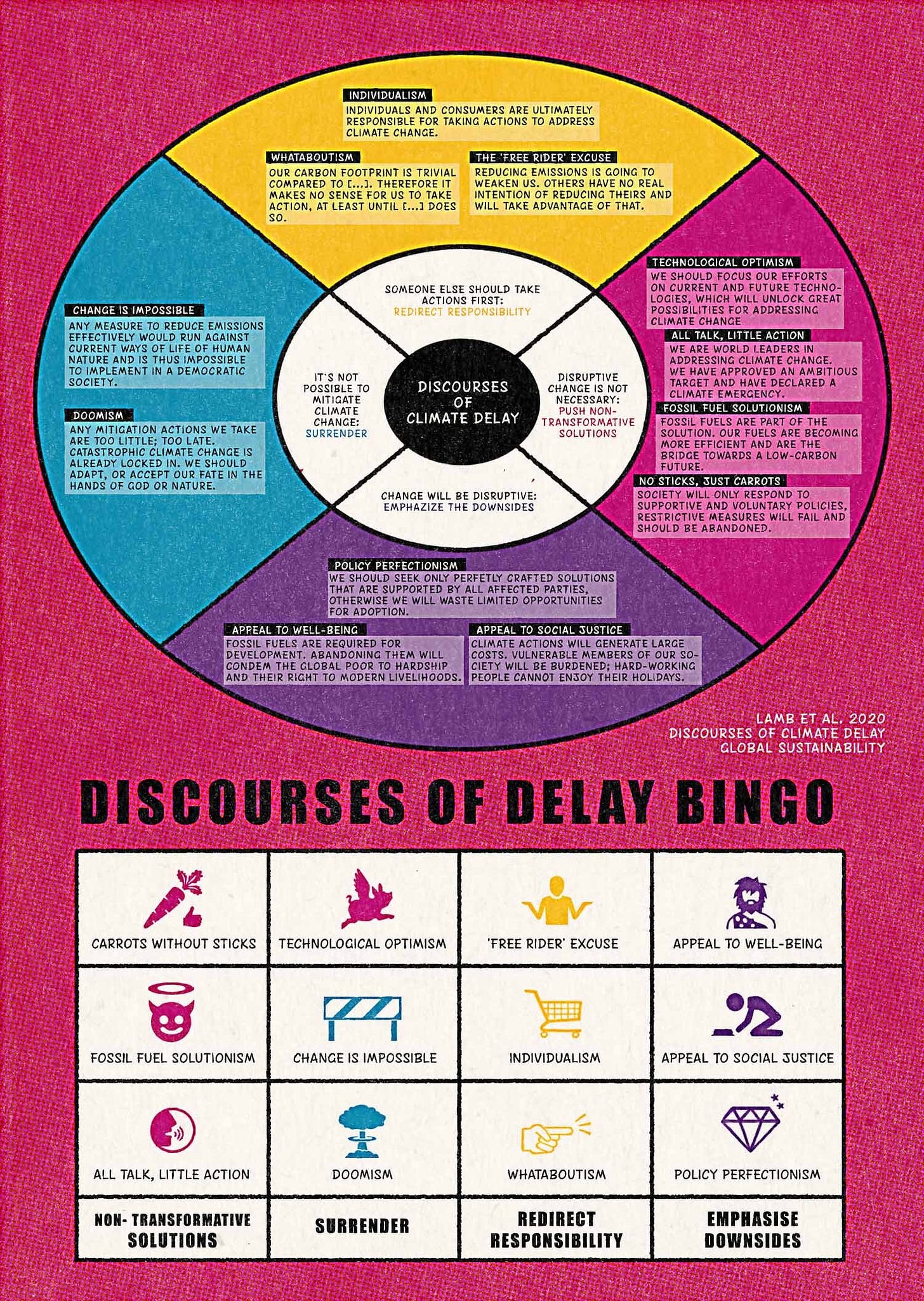

Which brings me to my final point - we need to take more care to scrutinise corporate narratives. This is because, although it may seem like more companies are ‘waking up’ to the reality that they are contributing to climate change and need to do something about it, many of them are still cleverly clinging to the broader framework of climate denial. The ‘new climate denial’ is not outright denying the existence of climate change, but delaying real climate solutions and distracting with false ones. If you’d like to understand this dynamic a little better, this comic adaptation of the Discourses of Climate Delay study by Céline Keller is a great place to start.

Some further reading…

Fashion is a social license for fossil fuels

“The will to act is itself a renewable resource.” - Al Gore This new TED Talk is well worth the 25 minutes for a damned account of how the fossil fuel industry has pulled the wool over our eyes and an inspiring call to put it back in its place. For me, the talk was a stark reminder that anything endorsing the continued extraction and combustion of fossil…

Thank you for reading Threadbare. There are now over 700 of you!

FYI, I’ll be taking a break of undecided length from this newsletter for a while. If you want to see why, follow my new Instagram :)

Thank you so much Lavinia 🙏 Ah sorry I missed adding the link before sending, but that exact sentence is grabbed from https://insideclimatenews.org/news/19032023/fossil-fuel-natural-gas-branding/.

The data underpinning that is due to their chemical makeup - essentially the global warming potential of gas/coal: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-03/ghg_emission_factors_hub.pdf

Gas is mostly methane > emits C02 and H20, while coal is more carbon based > emits pure CO2 (although I may be wrong as chemistry is not my strong point!) But I think the 'half as much' stat appears to be specific to the US: https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=74&t=11

For the 20-year period methane stat, see: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/methane-emissions_en and:

https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker-2021/methane-and-climate-change

The major problem I didn't mention with gas here is methane leaks:

https://www.npr.org/2023/07/14/1187648553/natural-gas-can-rival-coals-climate-warming-potential-when-leaks-are-counted

Which is why lifetime impact is important:

https://rmi.org/calculating-parity-between-gas-and-coal-life-cycle-emissions/

So good. So powerful. So needed to calling this out. May I ask the reference for "When burned, gas releases about half as much carbon dioxide as coal, but methane traps about 85 times more heat than CO2 over a 20-year period."? Thanks <3