[all opinions expressed are my own]

Hello! Thanks for subscribing to Threadbare in 2023. It’s been fun getting my newsletter up and running again, and I hope to develop this space further in the new year. Please do like, subscribe, comment, share this newsletter with people you think would find it interesting or useful. For now, it’s time for a bit of a break - wishing you all a wonderful Christmas and a happy new year!

I’ve just returned from an exhausting but fascinating COP28 where I joined my friends at Fashion Revolution to hold the industry accountable for its role in the climate crisis and crucially, its role in climate solutions including a just transition away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy and regenerative materials - see our joint demands here. I won’t go into the somewhat historic, somewhat disappointing COP outcomes here, but I highly recommend the coverage on Vogue Business from Rachel Cernansky, Maliha Shoaib and Bella Webb about what this means for fashion. I also wrote about fashion’s role at COP here.

I have a full book of notes from my 7 days in Dubai representing Action Speaks Louder, but I thought it would be most valuable to share some of my insights from a a panel event called Exploring a Just Transition in Fashion that I spoke on alongside Stand.earth, Fashion Revolution, Eco Age, Solidaridad East & Central Africa, Institute for Sustainable Communities, Diamond Denim and Transformers Foundation, whose recent report informed much of the conversation. This was a crucial discussion focused not just on the steps we need to take to reduce fashion’s significant carbon footprint - some of which is enabled through existing solutions and some of which are not yet possible through technical, financial or legislative barriers - but also on how we need to do it.

The key takeaway? Decarbonisation will not happen without close collaboration with and tangible support of the suppliers, from farms to mills to factories, who implement solutions on the ground.

What is a just transition and how is it connected to fashion supply chains?

When thinking about sustainability in fashion we need to think about impacts and dependencies. Obviously fashion brands depend on manufacturers to supply their products, they are the ones creating value for these brands. Because of that dependency, the majority of emissions - more than 99% in some cases - are produced in the supply chain and those brands who reap the benefits of that created value are responsible for reporting those emissions and ultimately supporting suppliers to reduce them.

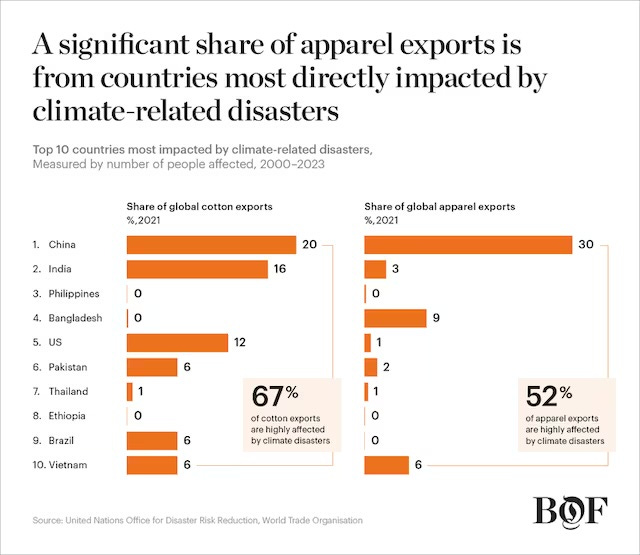

Because of the demands of mass production in our fashion system - not just fast fashion but also luxury brands which benefit from similar speeds and volumes - it is also the responsibility of those brands to be held accountable for the impacts upon the communities that surround those manufacturers. The manufacturing hubs in South and Southeast Asia in particular are in the very same regions most vulnerable to climate impacts such as flooding and extreme heat, as well as toxic air pollution from the burning of coal, biomass and in some cases, even textile waste. Brands source from these regions because of the low labour costs and weak social and environmental regulations, but they are now facing the reality that their business model is putting the future of their own supply chains at risk. (Source for below graphic)

In this way, I believe that decarbonisation in the fashion industry can be a form of climate justice in action, if it's done in a fair and just and ‘supplier led, brand supported’ way. We don’t want brands to reduce emissions just because it looks good on their latest sustainability report, we want them to do it because it will reduce the harm already caused to the communities upon which they extract value from.

It is their responsibility to take immediate and urgent action to phase out fossil fuels and ramp up renewable energy, instead of scapegoating the substantial carbon footprints - of the products they profit from - to the suppliers who they squeeze on margins and deadlines and then ultimately the workers who are paid far less than a living wage, leaving them very little resilience to the impacts of the climate crisis that they are providing labour for the corporations driving this destruction.

Describe how you want the fashion industry supply chain to look like in terms of the just transition 3 years from now.

Someone in our industry shared recently on Linkedin that the solution to fashion’s “climate problem” is surely just onshoring to countries with cleaner grids. But a just transition to a decarbonised fashion supply chain would bring the existing suppliers and workers along with it, to a more efficient, cleaner, greener and most importantly fairer system that benefits the communities without whom fashion as we know it would not exist.

It is also important to note that even if we used 100% sustainable materials - which we don’t - and even if we used 100% renewable energy in supply chains - which we don’t - we would still need to face the inconvenient truth that there is simply too much stuff. Brands like to focus on product-level improvements and intensity-based emissions reductions, but the reality is that we must reduce production volumes, and this is a key area where efforts towards a just and equitable transition must be focused because of the direct impact on garment and textile workers. I believe the The Or Foundation’s Speaks Volumes campaign is a great place to start - we need the fashion industry to own up to its overproduction and waste, and the impacts this has on communities around the world, as well as its ability to achieve climate targets. I hope that in 3 years time, we’ll see more brands be more transparent about production volumes and absolute emissions footprints, and that we’ll have more public pressure and support around the limits to endless growth.

What are some examples of the false solutions in the realm of fashion supply chain decarbonisation, and what do you want to see more investment in for solutions?

Firstly, the same amount of attention must be paid to fossil fuel powered manufacturing as to 'sustainable materials'. Its not just what fabrics are made from but how they are made, and tier 2 processing must be an area that we as a movement rally around as the biggest source of emissions. Our biggest ‘problem’ can become our biggest ‘solution’, rather than incremental progress on things like bio-based materials, or renewable energy for brands’ own operations only. These aren’t false solutions as such, but sometimes take up too much space in the conversion relative to their actual climate impact.

In terms of supply chain decarbonisation’s false solutions, I would draw attention to RECs (renewable energy credits), carbon offsetting, and biomass burning. The problem for all 3 is flawed accounting that allows companies to claim net zero while emissions keep rising. We need to triple renewable capacity (largely wind and solar) by 2030 and corporate procurement needs to support genuine additionality with strong renewable energy commitments and credible decarbonisation strategies.

We need to see a much, much larger corporate commitment towards investment in solutions, such as onsite solar panels, electrification (especically boilers) and zero combustion technology (eg. waterless dyeing, heat pumps) paired with robust policy advocacy for things like cPPAs (corporate power purchase agreements), larger scale onsite generation and cleaner grids overall.

All of this must be backed up by increased transparency on renewable energy procurement, taking into account the societal impacts of certain types of renewable energy production (eg. forced labour linked to solar panel production), health, land and nature impacts of biomass sourcing, and of course ensuring renewable energy and emissions reduction claims are credible. Where this isn’t currently possible, again we need to see these brands using their power, particularly in countries like Bangladesh where the fashion industry contributes such a significant % of GDP, to influence policymakers, and use their profits - of which they have billions - to fund their suppliers to make those necessary improvements on site and invest in new technologies that could also help them to remain competitive.

Overall, the lack of investment in renewable energy even where it is fully available must be our focus rather than just short term fixes, so bringing it back to filling those financing, policy, technical gaps is really key . We must avoid being distracted from the vision of a fully electric, zero combustion, low carbon future for the industry, which is a vision that needs all of our attention to realise.

Who pays for decarbonisation?

What the brands who we talk to are in large part unable to admit is their failure to set up proper financing mechanisms for their sustainability initiatives and therefore they lack the access to funds that are desperately needed in order to meet their own sustainability targets. Someone said to me yesterday that if a brand doesn’t have a climate investment plan, it simply doesn’t have a climate plan.

Ideally, we want to see at least 1-2% of revenue dedicated to decarbonisation and climate action. Profits are soaring, businesses are expanding and emissions are rising with it - we need financial commitment here backed up by proper mechanisms enabling suppliers to access financing/share financial risks/overcome barriers like currency and credit - there various examples from fashion and other sectors, such as H&M’s green fashion fund and Apple’s supplier clean energy fund. But we also need better purchasing practices - not just one-off funds but higher prices and longer term contracts on an ongoing basis - we need sourcing and buying teams to be included in these conversations - not only to provide the money for suppliers to invest due to a bigger margin, more confidence in longer commitments and therefore reduced risk, but also for the just transition to allow workers to reap the benefits of these hopefully increasing investments - without fair living wages, the decarbonisation conversation becomes redundant.

Individual brand actions are also not enough because we need to see multiple brands collaborate together, as they share suppliers and therefore can share costs and risks, and where they aren’t at the scale needed to access larger renewable energy projects, they can group together on PPAs or rooftop solar panels or renewable energy p infrastructure projects or finance new technologies like dry processing to scale up and be implemented in their supply chain. Aii’s Fashion Climate Fund and GFA’s new Bangladesh wind project are positive examples of this, but generally we need to see financing massively scale up in order for projects to move beyond that pilot phase, and ensure that headlines aren’t scooped up by ‘solutions’ that will not benefit the suppliers who need them most.

In general, it also comes back to purchasing practices, so understanding that in order for suppliers to make investments in decarbonisation, they need to be confident in their long-term, trusted relationships with brands including margins that allow them some wiggle room, and that as we travel further down the supply chain, suppliers will not be abandoned at the drop of a hat because they couldn’t afford to upgrade their factory.

This is where the main do-say gap is between the narratives brands push about their support for climate action vs the narratives their sourcing teams push upon suppliers to do more, faster, cheaper. In this way, responsible purchasing practices must be a part of any brands’ climate strategy.

How do we ensure accountability?

Brands often hide behind voluntary schemes when we ask them about their decarbonisation strategy, citing membership of RE100, verification with the Science-Based Targets Initiative, or association with the Fashion Charter, Textile Exchange or Sustainable Apparel Coalition for example, or even just the emissions factors in the GHG protocol. But as Changing Markets previously revealed in their excellent report on certification schemes, we must scrutinise who sets the rules, and who is ‘marking their own homework’. This is not necessarily to criticise any specific multi stakeholder programme, but to point out that they should not be substitutes for corporate accountability including full transparency on what brands are doing in their own business.

What would help ensure that brands are providing that information in order to be held accountable by civil society is robust legislation mandating, for example, scope 3 emissions reporting, emissions reduction targets, environmental due diligence, and at some point, hopefully a fossil fuel non proliferation agreement which Eco Age is working on with their brilliant Fossil Fashion campaign. I’m excited by The Fashion Act in New York, the new legislation in California and some of the developments around corporate accountability laws in the EU, and I hope that in 5 years time the landscape will be one of mandatory compliance rather than just voluntary schemes.

As an advocacy group in this space, we encourage people to join our campaigns in order to push brands to be held accountable for not just their negative climate impacts but their ability to enact positive change and be leaders that raise the bar for everyone. We’re currently working towards getting lululemon to commit to 100% renewable energy in their supply chain, and in a collaboration with Kpop4planet in Korea we are pushing luxury fashion brands like Dior, Saint Laurent, Celine and Chanel to set more ambitious emissions targets and be more transparent about their RE procurement and their support for suppliers to decarbonise. Ultimately, these brands’ scope 3 emissions are rising year on year, so without addressing that, we have to take sustainability claims with a pinch of salt and keep pushing for more transparency and more accountability for investing in solutions.

Thank you for reading!

If you’re a new subscriber to Threadbare, you can catch up on previous posts for free by exploring the archive.

SPREAD THE WORD!!!